PAQUIQUINEO (DON LUIS)

- Brendan Wolfe

- Nov 22, 2021

- 4 min read

Updated: Aug 18, 2022

Virginia Indian Traveled throughout Early Modern World

Paquiquineo was a Virginia Indian who for nine years traveled throughout the Spanish empire. In 1570, after converting to Christianity and changing his name to Don Luis, he returned to Virginia with a group of Jesuits. According to the few reliable primary documents associated with these events, Paquiquineo/Don Luis seems to have rejoined his family and, early in 1571, may have killed the missionaries.

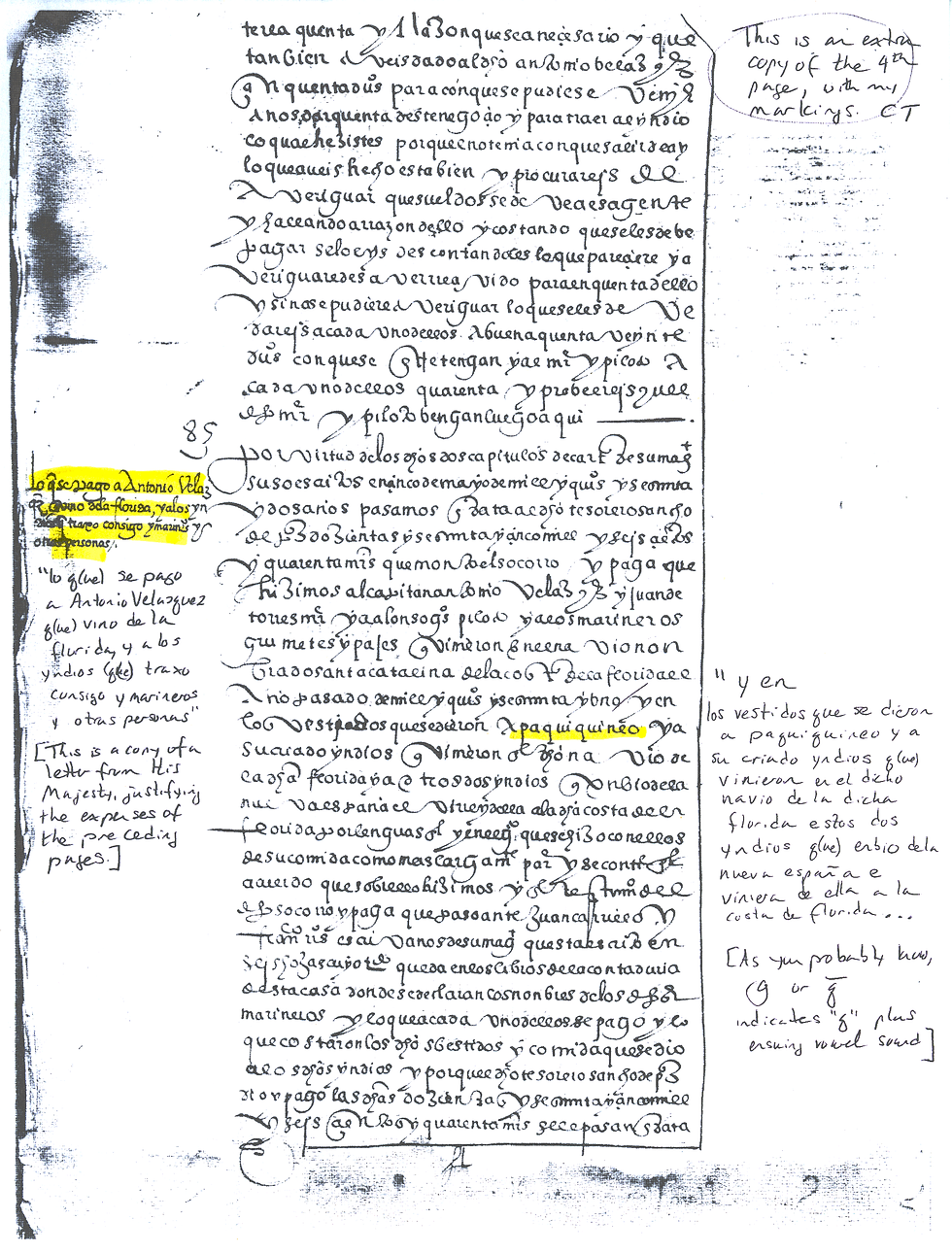

Paquiquineo and a companion encountered the Spanish on the James River in 1561. Historians disagree over whether the Spanish kidnapped the Algonquian speakers or whether the Indians accompanied them voluntarily. Whatever the case, Paquiquineo traveled to Madrid, where he had an audience with Philip II. The king permitted the Indian and his companion to sail to Mexico City. From there they could join a Dominican mission back to Virginia.

In Mexico, however, the Indians became ill and, thinking they might die, converted to Christianity. Paquiquineo adopted the name of the highest Spanish official in Mexico, Don Luis de Velasco. By the time he had recovered, the Dominicans had canceled their mission, and some historians wonder whether the illness may have been a ruse. Perhaps Don Luis hoped to prevent the Spanish from sending their troops and priests to his home.

Don Luis spent the next several years studying Spanish and theology with the Dominicans in Mexico City. Then, in 1566, another mission to Virginia was organized and Don Luis recruited as a guide. When the ship—also carrying Spanish soldiers—sailed north up the eastern coast of what is today the United States, the Spaniards could not find the Chesapeake Bay. They sailed too far north, too far south, and then too far north again before giving up and returning to Spain. Some in the crew blamed Don Luis for leading them astray; others blamed the weather and even the Dominicans.

Don Luis now settled in Seville, having fallen in with the relatively new Society of Jesus, also called the Jesuits. After several more years of studying, he was called again to join a mission to Virginia. In addition to Don Luis, the group included two priests, three brothers, and four others. This time, at the insistence of the mission's leader, Father Juan Baptista de Segura, no soldiers accompanied the group.

They landed on the James River on September 11, 1570. The next day, Baptista de Segura and another priest, Luís de Quirós, penned a letter to a Spanish official in Cuba updating him on their progress. The letter describes how Don Luis's people, suffering through a long drought, greeted him as if he had risen from the dead. The priests also mention a "careless" trade for food that seems to have upset the Indians. According to the anthropologist Seth Mallios, the Spaniards may have violated native norms by refusing to trade with Don Luis's people but trading with other

Indians. Hoping to protect potential converts from the sins of commercial activity, the missionaries may instead have gravely insulted their hosts.

The Jesuits were never heard from again. When a supply ship arrived and the missionaries were nowhere to be found, the Spaniards sent troops and rescued a lone survivor: an altar boy named Alonso de Olmos. His account, as told by others, suggests that Don Luis left the missionaries soon after arriving in Virginia. Then, in February 1571, he led a group of warriors who killed the Spaniards. A few scholars have argued that the Jesuits may have starved to death.

Either way, the Virginia Indian known as Paquiquineo and Don Luis disappeared from history. The Spanish never found him and the later English settlers only heard rumors. And in this way a truly remarkable life faded into legend.

Do Your Own Research

LEARN MORE

PRIMARY SOURCES

List of People on La Trinidad Expedition (August 1, 1566). Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 15 May 2015. Web. 4 Dec. 2014.

La Trinidad Expedition Log (August 14, 1566). Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 15 May 2013. Web. 4 Dec. 2014.

La Trinidad Expedition Log (August 24, 1566). Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 15 May 2015. Web. 4 Dec. 2014.

Letter from Antonio de Abalia to the Council of Indies (October 23, 1566). Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 15 May 2015. Web. 4 Dec. 2014.

Letter from Luis de Quirós and Juan Baptista de Segura to Juan de Hinistrosa (September 12, 1570). Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 30 Sep. 2011. Web. 4 Dec. 2014.

Letter from Luis de Quirós and Juan Baptista de Segura to Juan de Hinistrosa (September 12, 1570). Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 30 Sep. 2011. Web. 4 Dec. 2014.

Letter from Juan Rogel to Francis Borgia (August 28, 1572). Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 30 Sep. 2011. Web. 4 Dec. 2014.

Relation of Juan Rogel (ca. 1611). Encyclopedia Virginia. Virginia Foundation for the Humanities, 30 Sep. 2011. Web. 4 Dec. 2014.

SECONDARY SOURCES

Douglas Bradburn and John C. Coombs, Early Modern Virginia: Reconstructing the Old Dominion (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2011).

Anna Brickhouse, The Unsettlement of America: Translation, Interpretation, and the Story of Don Luis de Velasco, 1560–1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014).

Ralph Hamor, A True Discoure of the Present State of Virginia (Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1957).

Seth Mallios, The Deadly Politics of Giving: Exchange and Violence at Ajacan, Roanoke, and Jamestown (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006).

Daniel K. Richter, Land, Power: The Struggle for Eastern North America (Philadelphia: University of Philadelphia Press, 2013).

Helen C. Rountree, Pocahontas, Powhatan, Opechancanough: Three Indian Lives Changed by Jamestown (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2005).

Comments